Why have Chinese construction firms become so influential in Africa?

14 March 2023

When it is completed later this year, it will have taken just four years for Africa’s first supertall skyscraper to rise out of the desert.

Egypt’s 385m-high Iconic Tower, part of the country’s New Administrative Capital (NAC) outside Cairo, symbolises the huge influence Chinese finance and Chinese construction companies have started to wield on the African continent.

The China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC) is overseeing construction of the skyscraper.

It is part of a $3bn investment deal under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) by China to build the central business district of the new city.

China’s growing influence

China’s global infrastructure development strategy, the BRI, has seen 52 countries in Africa sign up.

Whereas in 1990, American and European companies won more than 85% of construction contracts on the continent, China’s influence has grown significantly. Funding for infrastructure projects in sub-Saharan Africa by bilateral development financial institutions (DFIs) has seen a sharp increase since 2007, led by China. It provided a cumulative total of £23bn in investment in Africa between 2007 and 2020, according to the Centre for Global Development. And in 2019, it funded one out of every five projects (20.4%) in Africa, just behind the share of projects funded by African governments (22.8%), according to Deloitte.

With China’s burgeoning financial clout in Africa has come more work for Chinese contractors. In some cases, lending is tied to the contracting of Chinese companies.

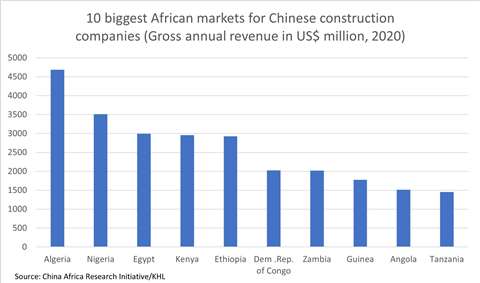

In 2020, the China Africa Research Initiative (CARI) at Johns Hopkins University in the US put the total gross annual revenues of Chinese construction companies in Africa at US$38 billion. This made up 24.6% of global revenues for these companies. Although that was down from the peak in 2010 when the continent accounted for 38.9% of their global revenues. According to a new report by the Green Finance & Development Centre (GFDC), part of the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University, Shanghai, China, Chinese investment in sub-Saharan Africa has fallen since the covid-19 pandemic. The report found that sub-Saharan Africa saw a 44% drop in construction and a 65% decline in investment compared to 2021. But that was countered the Middle East and North Africa receiving 23% of Chinese investment volume under the BRI in 2022, twice the share of 2021.

Carlos Oya, professor of political economy of development at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London, says, “There has been a surge in the activities of Chinese contractors in Africa’s infrastructure market, especially since 2005.”

He attributes that surge to different drivers, including tied development finance for economic infrastructure. But he notes that as leading Chinese contractors gained market share, they started winning tenders from non-Chinese sources too.

“They became major infrastructure construction players and came to dominate the market in 10-15 years. There are various reasons for this success. One is the fact that these contractors are able to deliver complex projects with excellent technical specifications in short timeframes, something that African governments and their elites have appreciated. The massive construction boom in China since the 1980s constituted a major advantage in terms of gaining technical experience, scaling up construction activities and learning to manage complex projects,” he adds.

What is driving Chinese contractors’ success?

1) Scale of lending:

Lending by Chinese creditors in Africa totaled US$153 billion between 2000 and 2019, according to CARI. It has since fallen from its peak as several African countries struggle with debt sustainability. But a significant proportion has been dedicated to construction projects. Over that time, the number of Chinese financiers has also swelled from just three in the year to 2000 to over 30 in 2019, many of which were lending commercial rates, according to SAIS-CARI.

The biggest lenders are China Eximbank and China Development Bank. In countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana and Guinea, Chinese lenders have adopted a resource-backed lending model. That sees borrowing countries commit future revenues from their natural resources to repay the loans. With the influx of Chinese money have come Chinese construction companies, vying to fulfil the contracts.

Frank Kehlenbach, director of European International Contractors explains: “China offers package deals, which are attractive to African clients because they are organised more or less as a one-stop shop. After the financing agreement between the Chinese and the African government the loan is provided quickly by a Chinese policy bank and then the contract is awarded to a Chinese state-owned contractor. Sometimes, the African country pays back the loan with natural resources in a barter deal. Such one-stop project delivery is not possible for a country like the UK or Germany. Development policy processes in Europe are time-consuming and much more complex.”

2) Competitive pricing:

Chinese construction companies have often proven able to offer more competitive tenders than their western or African counterparts. According to European International Contractors (EIC), Chinese contractors are under-cutting market-dependent businesses from elsewhere in the world by up to 20% in open competitions.

Because some Chinese finance deals are tied to the use of Chinese contractors, the companies already benefit from having supply chains and labour in place in Africa. That helps them to bring down cost.

Late last year, the South African National Roads Agency (SANRAL) hit back at discontent in the country that Chinese firms had won tenders for hundreds of millions of dollars work of contracts awarded by the Development Bank of South Africa. It noted that it was legally obliged to award the contract to the company that performed best in the tender process. And it said: “The contracts were awarded to the tenderers which submitted the highest scoring eligible bids…SA companies are free to form joint ventures with any other company either locally or internationally”.

3) Speed of construction:

CSCEC took just 808 days to build the entire concrete core for the Iconic tower in Egypt. It built the steel framework at a rate of one floor every three days. That reflects the speed at which Chinese firms are able to build, sometimes working off pre-existing designs for structures they have already built elsewhere. That speed appeals to local leaders, anxious to see their projects completed before the next election.

4) Western companies’ attitude to risk:

Construction work in Africa can carry risks including political instability and escalations in conflict. Some western companies also hold concerns about business practices. Meanwhile, beefed-up anti-corruption laws in places like America and Britain mean that paying bribes can land them in serious trouble.

In 2022, Bouygues Bâtiment International was sanctioned by the World Bank in connection with “collusive practice” over an airports project in Madagascar, for example. Contractors from countries like the UK and Germany are doing less business in Africa. But others maintain a significant presence. They include French, Portuguese, and Italians.

Opportunities for non-Chinese construction companies?

Professor Oya notes, “The other side of the coin is the massive infrastructure gap in Africa, after decades of neglect, not least by the key development finance players that were expected to fund infrastructure projects, for example World Bank. African governments, increasingly keen on implementing structural transformation and industrialisation strategies have found the availability of Chinese finance and the emergence of Chinese contractors as an opportunity to fulfil these aspirations.”

But non-Chinese powers have started to wake up to this, even as Chinese lenders are starting to pull back from the continent. In 2022, the G-7 launched the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII). Members pledged US$600 billion in loans and grants for quality, sustainable infrastructure projects in developing and emerging economies. The move has been seen as a counter to China’s growing influence via the BRI over the past decade.

The aim is to bring new projects on the continent on stream, providing more opportunities for engineers and contractors from all over the world. The Export-Import Bank of the United States and US firm AfricaGlobal Schaffer have already signed a contract to develop a $2 billion solar project in Angola.

The UK also signed a deal with Kenya in late 2022 to progress $4bn of investment across six projects, including a new geothermal and solar energy plant, and a public private partnership to deliver the Grand High Falls Dam, which will generate a gigawatt of renewable energy.

Skepticism about G7 partnership

The Chinese CCECC-CRCCIG won a deal to build the $2.5bn Fourth Mainland Bridge in Nigeria at the start of 2023 (Image courtesy of Nigeria’s Office of Public-Private Partnerships)

The Chinese CCECC-CRCCIG won a deal to build the $2.5bn Fourth Mainland Bridge in Nigeria at the start of 2023 (Image courtesy of Nigeria’s Office of Public-Private Partnerships)

But Kehlenbach is skeptical about the level of new business that the G7 initiative will bring for non-Chinese contractors.

He says, “The G7 partnership aims more at privately financed projects. If there is one market on a continental level that private investors would generally consider as too risky for long-term infrastructure investments, it is Africa. That is because the legal and financial framework conditions do not allow for a 20- or 30-year concession. In addition, the planning horizon focuses on the period up to the next election. I don’t think the G7 initiative, as currently drafted, will have a big impact for infrastructure projects in classical infrastructure sectors, such as transport and water, in Africa.”

That is why the EIC is in the process of launching a toolkit to advise development banks on sustainable procurement. It will promote the idea of evaluating bids for tendered projects on quality and value, rather than price. In doing so, the EIC hopes to level the playing field for European companies.

Kehlenbach adds, “The most important message EIC tries to get across to the multilateral development banks (MDBs) is to tender large construction projects not on price but on sustainability. Tenders awarded on the basis of the lowest price will naturally be awarded to Chinese bidders. We are currently working on a toolkit on sustainable procurement where we explain to international and European donors and to procurement staff how to tender infrastructure projects on sustainability, rather than just on price.”